05:00PM, Thursday 06 February 2025

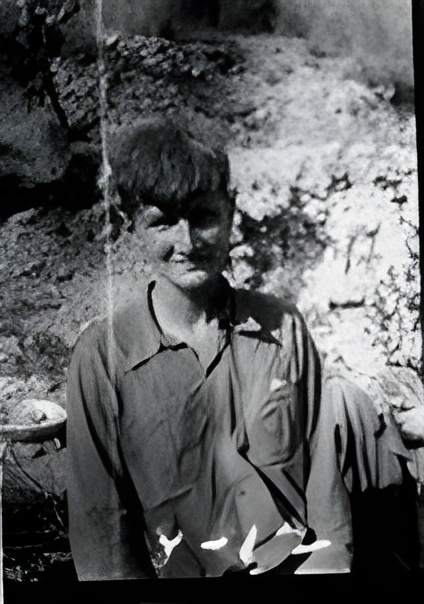

A campaign is underway to get George Norman Rodney Drury-Fuller (inset) a memorial near to Maidenhead Town Hall.

There is a famous George – Orwell – who fought in the Spanish Civil War, but there is another ‘forgotten’ combatant with connections a little closer to home.

George Norman Rodney Drury Fuller: a young medical student from Maidenhead who volunteered to join the war aged just 18 and who fought in one of its most ferocious battles.

A campaign is underway to get a memorial of his own near the war memorial at Maidenhead Town Hall, so that he can be remembered alongside others who fell fighting fascism.

It was a fight which – unlike Orwell – George from Maidenhead would never return from.

The only known picture of George (credit: Philip Wilson-Marks and International Memorial Brigades Trust).

George lived in Linden Avenue in Furze Platt with his mother Beatrice. Drury was his father's surname and Fuller his mother's maiden name.

He studied medicine at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London and was a Communist Party member.

George joined the International Brigades, a multinational alliance of soldiers more than 30,000 strong, fighting in the Spanish Civil War in 1937.

Piecing together George’s story has been Philip Wilson-Marks, 39, a former Cox Green resident and Global Studies teacher in Manchester.

Philip is researching historical RBWM residents ‘looking for radicals’, and while trawling the Soviet Archives he uncovered George’s name and hometown.

“I stumbled across his name and that he came from Maidenhead – that really was the thread that unravelled his story,” Philip said.

British Union of Fascists supporters make the ‘Roman salute’ in Trafalgar Square 1938 (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

In the 1930s fascism was rising in Europe and at home.

Britain had been dragged through more than a decade of economic hardship with fervour intensified through cuts to state benefits during the great depression.

Hitler took control of the German government in 1933; Italian dictator Mussolini had ruled since 1922; Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists swelled with support.

And in 1936, a coup led by fascist general Francisco Franco and backed by the Nazi powers threatened to oust the left-leaning Spanish Republic.

George heard the call to sign up to the newly created International Brigades and take the fight to the fascists.

He defied UK authorities, which had banned joining the war in Spain, to join around 2,500 others in the brigade's British Batallion.

Historian Richard Baxell, 62, former chair of the International Brigade Memorial Trust, has spent 30 years researching the Spanish Civil War.

Historian Richard Baxell (credit: Richard Baxell)

He said: “I think it was a cocktail, I would say, of a feeling that the world wasn’t a fair place – and that if they went to Spain to fight fascism there, they wouldn’t have to fight it somewhere else.

“Yes, they’re going to fight in another country’s civil war but it was always seen in a wider political context.”

George joined as a medic but enlisted in the brigade’s military division after a year.

Richard said serving in the medical services would have been tough.

He said: “They were often operating without anesthetics; a lot of the battles were bloodbaths and it must have been exhausting work.

“Some doctors talked about working for 48 hours or more without more than an hour's sleep snatched here and there.

“I suspect he got to the point where he was angry enough, he wanted to do more.”

Spanish Republican forces cross a pontoon bridge over the River Ebro (credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Under the hot Spanish sun, amid the crooked gorges and valleys of Catalonia, played out the Battle of the Ebro: the ‘last throw of the dice’ for the Republican forces.

Beaten back over years of slogging combat and in imminent danger of their forces being severed in two, the Republicans plotted a desperate attack across the River Ebro in 1938.

The hope was to break Franco’s tightening grip on the republic - or at least buy time for Britain, France, and the Allies to offer support if they became embroiled in a wider war in Europe.

“It was only a matter of months before that did happen,” Richard said.

“But really, the Ebro, the whole launch of that battle was taken in the knowledge that it was a gamble.

“A few people have called it the last roll of the dice for the republic and I think it was very much that.”

Outgunned and outnumbered, thousands of soldiers teetered across pontoon river crossings as fascist fighter planes rained down bullets and bombs.

The British Battalion was tasked with capturing the heavily fortified Hill 481 overlooking the small town of Ganesa.

But at Hill 481, the Ebro offensive would begin to falter. Despite gruelling assaults, International Brigade soldiers couldn’t dislodge the fascist occupiers.

Now on the defensive, the men saw more fierce combat holding their positions.

The conditions were ‘absolutely awful’, said Richard.

“They wouldn’t have had enough food with them; most of the soldiers were dressed in rags; they hadn’t got any shoes – they’d cobbled together espadrilles from bits of old car tyres.

“I’ve walked the ground [of the battle] on many occasions and it is terrifying, trying to put yourself into their shoes.”

George was killed in action on September 23, 1938 – the last day of the British Battalion’s participation in the Ebro offensive.

He was 20 years old.

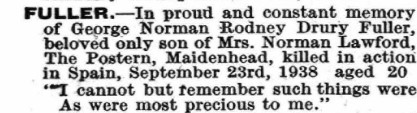

A notice placed in the Maidenhead Advertiser dated September 23, 1942.

Exactly what happened to George during his final battle is – so far – unknown, like many others who fought and died in the World Wars.

Philip said records with the International Memorial Brigade Trust had showed George was assumed dead, but through his own detective work he found confirmation.

Philip Wilson-Marks has been piecing together George's story (credit: Philip Wilson-Marks).

“It was all a bit patchy,” Philip said.

“They thought he was missing presumed killed, but then of course, when I went back through the Maidenhead Advertiser archives I saw all the obituaries from his mother confirming he had died in Spain.”

George’s mother Beatrice posted three obituarties in the Advertiser between 1939 and 1942 to remember her only son, ‘in proud and constant memory’.

Philip does not know what happened to Beatrice after World War Two.

He is hoping to raise £750 to get a permanent memorial for George near to the war memorial in St Ives Road – and near to the ‘other heroes in the fight against fascism’.

He said: “It’s stories like his that people may not necessarily be aware of and get forgotten or lost to time.”

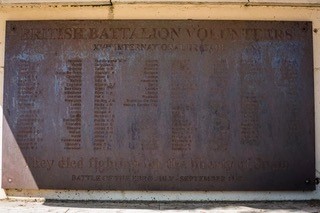

George’s name is inscribed alongside the names of 89 other British and Irish soldiers who died in the Battle of Ebro on a memorial plaque at Hill 481 in Spain.

The memorial plaque for the British International Brigade (credit: International Memorial Brigades Trust).

The original plaque, moved to the UK in 2016 after it was vandalised by Spanish neo-fascists, can be viewed on display at the Marx Memorial Library in London.

It reads: ‘They died fighting for the liberty of Spain’.

You can view the fundraiser for George’s memorial at: tinyurl.com/mseusjsa

For more information on the Spanish Civil War and the International Brigade visit the International Brigade Memorial Trust website.

Most read

Top Articles

A housebuilder will have to demolish a home that was put up without permission within three months – having lost an appeal against the council.